Every once in a while, we writers get inspired with an idea that just wouldn’t let us go. But while writing it down is always totally fine, there are instances when you’ll need to stop and think and ask yourself if this story that you should publish. I’m talking about stories where the point-of-view character is marginalized, and you, the author, don’t share this marginalization.

There are a lot of discussions online about this. Some say it’s okay, while others say it’s not. I can’t speak for anyone else but myself, so here’s what I think! 🙂

This piece, So, You Wrote A Marginalized Protagonist, was first published on Be Your Own Mentor. Many thanks to Rosiee Thor for helping me edit it!

So, you wrote a marginalized protagonist…. But you’re not marginalized yourself.

Maybe your dream agent mentioned wanting one on their manuscript wish list. Perhaps you saw a book deal announcement featuring one on the weekly rights report. Or maybe you wrote this book to give marginalized readers a character they can relate to.

“Yes! I’m so excited to edit and then query and then publish it and then—”

Easy, tiger. One step at a time. Let me tell you a story first. My story as a reader.

Even as a kid, I loved books. I read anything and everything I could get my hands on. Fantasy, science fiction, contemporary, mystery—you name it, I read it. I lived in the Philippines (I still do), and books from the United States dominated our stores (they still do). Those stories fascinated me. I felt like I was given a window to a world so different from my own.

Still, there was one thing Kid Reader Gail always wondered about. Were there no Filipinos like me in the US?

I had cousins, aunts, and uncles who lived there. They spoke English, and had cereals for breakfast instead of steamed rice, fried egg, and dried fish. But it was hard for me to imagine them going on adventures like the fair-skinned boys and girls I kept reading about. They just weren’t there—brown heroes and heroines didn’t exist.

Kid Reader Gail never saw herself in the books she read.

“That’s a touching story, Gail. So sad. What does it have to do with me?”

I’m getting there.

If your reason for writing this story is to have marginalized readers to see themselves in your protagonist, you’re on the right track. But before you start querying that amazing, agents-will-fall-all-over-themselves-to-rep novel with a marginalized protagonist, take a moment to ask yourself this: what is the point of your story? I’m not asking that to be mean, but I need you see how your character’s marginalization intertwines with your story theme.

“Story theme? What’s that?”

It’s not really what this piece is about, so here’s the short version. Plot is what your character wants, while theme is what your protagonist needs. Simply put, theme is the heart and soul of your story.

A character’s marginalization can and will affect your story theme. How they’ll sacrifice their Want to attain their Need depends on the experiences that shaped them as a person. For example, let’s say you want to have a 12-year-old Filipino protagonist who lives in Metro Manila with his weird grandma and his stingy parents. His name is Juan.

Juan wants a bike as awesome as the ones his rich friends have (the Want). But his parents won’t buy him one, so Juan goes through all these obstacles you throw at him. Soon, he realizes that it’s not because his parents didn’t want to buy him the awesome bike, it’s because they can’t afford it. Juan eventually learns he doesn’t need “friends” who’ll only like him if he has a nice bike. There are people who loves and accepts the way he is, and that’s what matters the most (the Need).

It’s pretty rough and typical of an “acceptance” story, but there are a few things at play here you might have missed:

- Juan’s need to be accepted by rich friends. Here in the Philippines, having money gives you power. The divide between the social classes are far apart, and corruption is so entrenched in our system. It’s really difficult to move up without help. It’s common to see themes of social divide in a culture like ours.

- Juan’s parents didn’t tell him point-blank why they couldn’t buy him a bike. It would have been easier, right? I mean, if they just told him, Juan wouldn’t have to go through all that trouble. But as somebody who has been poor, it totally makes sense to me. There is shame in admitting your financial difficulties. Like, you have failed somehow. It’s a burden you wouldn’t wish your kid to carry.

- Juan’s grandma lives with them. Inter-generational families living under one roof is very much the norm in my country. We have close family ties. While living alone is more common in the cities, it’s not the case for most of us in the suburbs or the rural areas. Had Juan’s story been a real book, you can bet the grandmother and everyone else who lives with him will have some role to play in Juan’s quest to turn his Want into a Need.

There is a layer of nuances in our example above, a layer unique to the identity your protagonist ideally should have.

This brings me to my next question: can your story stand on its own even if the character doesn’t have the marginalization?

Thing is, writing a marginalized protagonist isn’t as simple as slapping identities to your character. You can’t just say, “he’s Filipino. And gay. Oh, he’s blind too.” You need to bring to life the subtle differences that make your character Filipino, gay, and blind. At the same time, you need to show how these identities intersect. Your marginalized protagonist must live, breathe, feel, think, and speak these nuances.

“But freedom of speech, Gail! I can write what I want!”

That is true. No one can stop you, nor should anyone stop you, from writing / querying / publishing what you want. But hold that thought. Let me tell you more about the story of Kid Reader Gail.

I was already in high school when a novel for young readers came out with a Filipina-American protagonist. I got excited. I mean, finally, a main character I could relate to! Well, not exactly. But she was part-Filipina, and that was more than enough for teen me.

Then, I started reading. They misspelled some Tagalog words, but it was okay. The protagonist didn’t seem like she had trouble navigating life while being brown. Sometimes, it was hard to imagine her being brown at all. Still, I shrugged. The book was only fiction, after all. Maybe the characters lived in a utopia where micro-aggressions to brown people never existed. But when the main character began doing weird and offensive things that were supposed to be “Filipino,” I’ve stopped making excuses and closed the book. It was a DNF—Did Not Finish. I could not finish.

It’s true that people experience marginalization and culture differently. What is true for me, may not be true for you. But when you’re writing someone else’s experiences outside your own, it becomes an entirely different ballgame.

“So, are you telling me I shouldn’t have written outside my lane?”

No. You technically could, if you felt you must. But you need to have done the hard work.

I’ve already discussed how your character’s marginalization intertwines with your story’s theme and overall plot. However, it doesn’t stop there.

This short list isn’t definitive, but hopefully, it’ll point you to the right direction as you edit your book.

Avoid stereotypes

Relying on stereotypes isn’t just offensive—it’s a failure in characterization, and laziness in writing. Harsh, right? Maybe, but you also need to put yourself in the shoes of people you might offend.

By “stereotype,” I don’t just mean racist words or ethnic slurs. It’s also the subtle things, the micro-aggressions we don’t notice because we’re not affected. For example, describing a man with “he looks Japanese.” It may seem harmless, but these sweeping statements imply that Japanese men all look the same. You are basically relying on the reader’s preconceived stereotype of what a Japanese man should look like. You need describe your Japanese characters like you would your other characters.

“But I might get them wrong!”

Yeah, you might—if you don’t do your research.

Research, research, research!

I don’t mean just scouring Wikipedia for answers. Go deeper. Search and read articles and blog posts from people who share your protagonist’s experience. Visit the place you want to set your story in, meet the people and get to know them. Research about the experiences and cultures as much as you can.

Get a targeted beta reader

A targeted beta reader, popularly known in social media as “sensitivity reader,” is like a beta reader but focuses on the cultural accuracy of your story. They are authors, editors, or avid readers who share the marginalized experience of your protagonist. The reading they do is emotionally exhausting, and speaking as someone who’s done it—it can be triggering. Don’t expect them to read for you for free.

Like any editor or beta reader, you, as the author, have the prerogative to accept or ignore their suggestions. You can even be stubborn and insist on the problematic stuff. I get it. It hurts to be called out. But remember, you have a chance to fix things. Take the opportunity to learn from your targeted beta reader’s notes, and your book will be better for it.

Thing is, even if you have your book read for cultural accuracy, it still doesn’t shield you from criticism. But it’s a start.

Read books by marginalized authors

This is probably the crucial—and the best—part of the process when writing a book with a protagonist whose life experience you don’t share. Read books by marginalized authors. It’s a great way to “pick the brain” of a marginalized author without invading their privacy or obliging them to help you. See what it’s like to be in their shoes by reading their experiences translated into fiction. You’ll be surprised at how different they are from your perceived notion of their experiences.

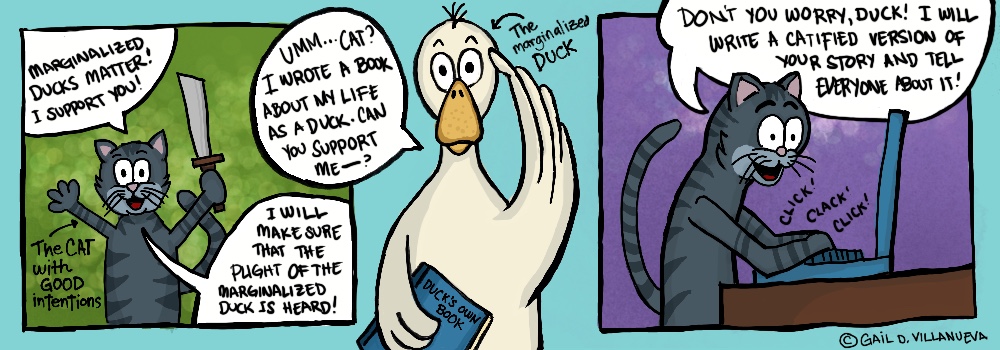

Support marginalized authors

Uplift them. Follow them on social media. Listen to them. Support their work. Promote their work. It’s hard to authentically write an experience when you don’t walk the talk.

I’m not going to deny it—this is a lot of work. Even though you have a partner / wife / husband / best friend / neighbor / dog / cat who “has lived experience,” you’re not absolved from doing the work. I mean, I’m brown, and I still don’t get a pass. We all need to do our homework, especially when we’re writing outside our experiences.

Once your book is out in the world, it’s not just yours anymore. By publishing, you’ve chosen to share it. And by sharing, you will affect people with your words. Even if you wrote this book with good intentions, there’s still the potential to hurt.

I was already sixteen when I first encountered a hurtful stereotype of Filipinos in children’s literature. I encounter them more often now in the books I critique for cultural accuracy check. It still hurts when I see them, but I’m used to it.

Imagine what it would be like for a kid, or for somebody who will take your words like knives to their hearts. Books can be life-changing to our readers. Sometimes, they even become lifelines to those who need them.

It’s scary, I know. But that’s part of being a writer.

Like I said, no one is going to stop you from writing and publishing a book with a marginalized protagonist. However, it’s important to note that every time an author outside the marginalized group they’re writing about gets their novel published, it’s one less space for an author who actually lives the experience.

So. It all boils down this final, but most important question. Are you the right person to write this story?

You might have written the book for a noble reason. You’ve done—and you’re willing to do more of—the hard work. Sure, you might even be able to do the perspective justice. But sometimes, we need to concede to the idea that it might be better to step aside from writing this marginalized perspective, and show our support for authors who share those experiences. Hard as it may be to accept, there are just some stories that aren’t yours or mine to tell.

Be compassionate. Learn to empathize. Recognize your privilege. These are just a few things that would help you understand if this marginalized perspective is a story best told by you, or its shelf space should belong to an author who has lived experience.

Don’t be afraid to take out the editing knife if you have to. Remember, you are your own person, unique with your world views and life experiences. They add flavor to your stories, giving your readers a perspective that’s totally, undeniably, you.

Find your voice, and listen to your heart. Write those stories only you can tell.